Exploring masculinity and male intimacy with Ben Sharp

This article contains image descriptions in the captions to help those with visual impairments.

After witnessing heterosexual male on male relationships growing up and during his time at University, photographer Ben Sharp wanted to explore the balance between straight male intimacy and how society and culture within the west impacted on these relationships forming and their longevity. We recently spoke with Ben to explore these themes that come to play in his body of work, No Homo.

Interview by Harry Rose

The work follows your own experiences and outlook on masculinity and male intimacy, what made you want to explore this?

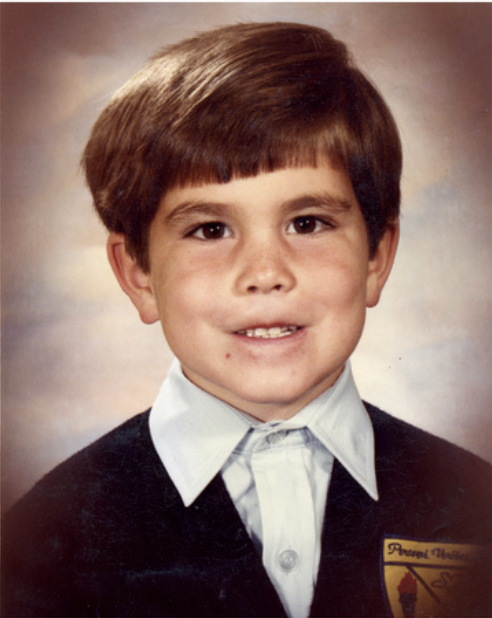

The work established from a close but complex relationship I formed with a straight male during my time at university; this friendship inspired my project ‘pretty boys’, an exploration into masculinity, but the investigation into male intimacy and the relationship between straight and queer males wasn’t fully explored until ‘no homo bro’.

I struggled to create and sustain close bonds with straight males, so this friendship was interesting for the pair of us as neither of us had never had a close friend of the same sex with a different sexuality to our own. Whilst our opposing sexualities wasn’t a factor which impacted the initial friendship, it became apparent as we grew closer, through our discussions, that highlighted our upbringing and experiences in life differed massively; one of these points being that our views and experiences of male intimacy were polar opposite.

Whilst he didn’t necessarily conform to every traditional masculine stereotype, I remember us having a conversation rather early on about how he wouldn’t open up about hardships or personal issues to “the lads” from home, and nor did he have the desire or need to do so. I, however, being someone who had grown up to be both physically and emotionally intimate with my close friends found this fascinating, and this really begun my exploration into masculinity, before focusing specifically on male intimacy between men.

What were your observations of ‘lad culture’ growing up?

Within my research for the project, there was an extract from R W Connell’s Masculinities which touches upon male friendships, discussing how heterosexual men don’t predominately have close 1:1 bonds with other men, likening these friendship groups to that of a wolf pack – and I think this is something that I would relate to through my observations. The research suggests that within heterosexual male friendships, men are more likely to form a bigger group of friends with a leader, without any of these bonds being built upon substance or depth, whereupon the individuals within the group are disposable and can be easily replaced by another figure. To an extent, I agree through my own experiences - If you are to differ or challenge the cultural norms of the masculine ideal, then you aren’t accepted, and subsequently excluded, from the ‘pack’.

Growing up, for me, the majority of male friendships that I witnessed, which conformed to traditional masculine archetype, were bonds built from their passion for sports, interest in girls or humiliation/intimidation of others – which in some cases can manifest into misogyny and/or homophobia. At the time, I was rather intimidated by these individuals but as I grew older my I emphasised them, because my understanding of ‘lads’ evolved to realise that for some, their actions mask their insecurities which have be indoctrinated by society. There’s a quote from Nan Goldin’s introduction in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency that I’ve cited throughout my practice which epitomises this notion; “For many years, I found it hard to understand the feeling systems of men; I didn’t believe they were vulnerable and I empowered them in a way that didn’t acknowledge their fears and feelings” (1987).

You mentioned that growing up queer and being unable to obtain and sustain close relationships with straight men. Do you feel this was more based on societal pressures on straight men to maintain a level of masculine dominance? It often took a lot during the 90s and 00s for a straight guy in school to openly form a friendship with a Queer person.

I would definitely say it was a contributing factor; I think because I didn’t conform to the masculine ideal, not having a huge interest in sports for instance, and that generally speaking I was rather sensitive and attentive, it was difficult for me and straight men to bond because of the societal pressures placed on them to remain masculine. And in the case that I would begin to form a close bond with a straight male, there was the possibility that they would also likely be labelled as ‘gay’ - a term, during this time, deemed as negative - so understandably rather than being possibly ridiculed for this, they were more likely to distance themselves from queer individuals.

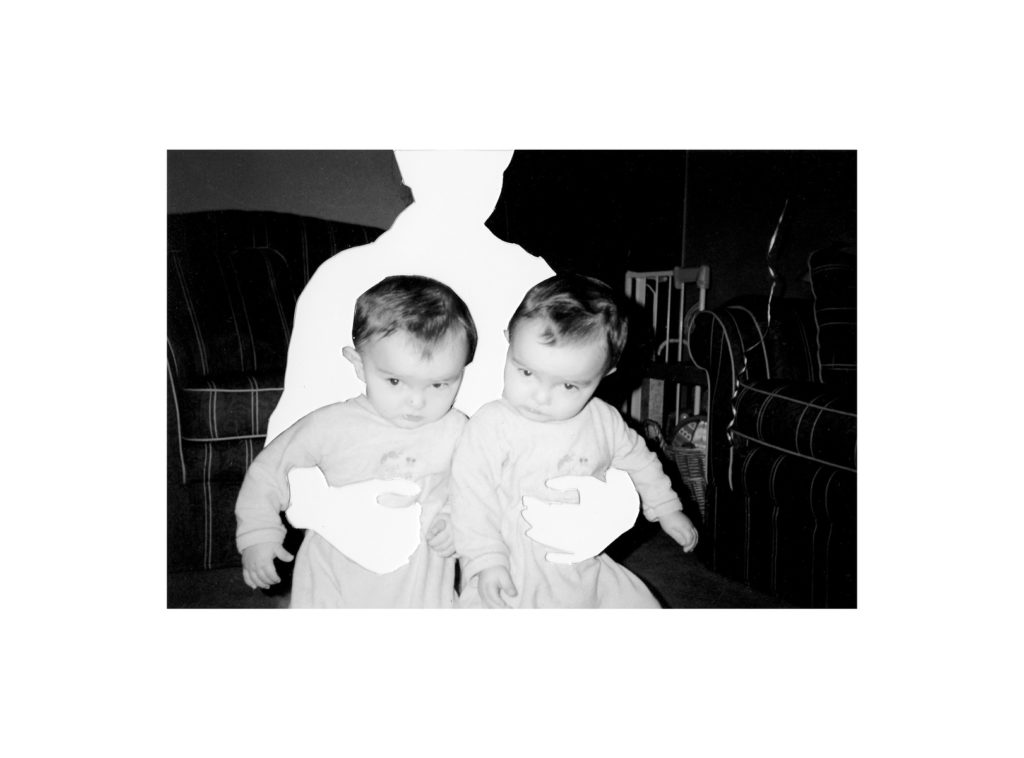

Your photographs show a deep and clear connection between each subject, with a boundary between bromance and homosexuality being explored. How much of these images reflect your own experiences growing up as well as society today?

For me, I’ve always felt my practice has been a form of therapy or self-exploration, and this project is definitely an example of this; as I mentioned above, the work stemmed from a friendship at uni and to an extent the imagery reflects my journey of exploring the limitations and boundaries of this relationship. The dynamics of our friendships were complex over the years because the boundary between bromance and homosexuality between the two of us was explored and challenged.

Subsequently, my physical and emotional experiences with ‘straight’ men has occurred on multiple occasions and I think it does reflect the times we live in; we live in a time where sexuality isn’t demonised to the extent it was even a decade ago. However, on the other hand, with an increase of acceptance, there’s this new territory I think we’re currently exploring where heterosexual men are more comfortable with queer individuals, but because of ‘toxic masculine’ ideals being deeply rooted into society, a form of internalised homophobia can still prohibit their relationship with queer individuals – whether that be sexual or not.

Tell me more about some of the people you photographed, their connection to you and one another.

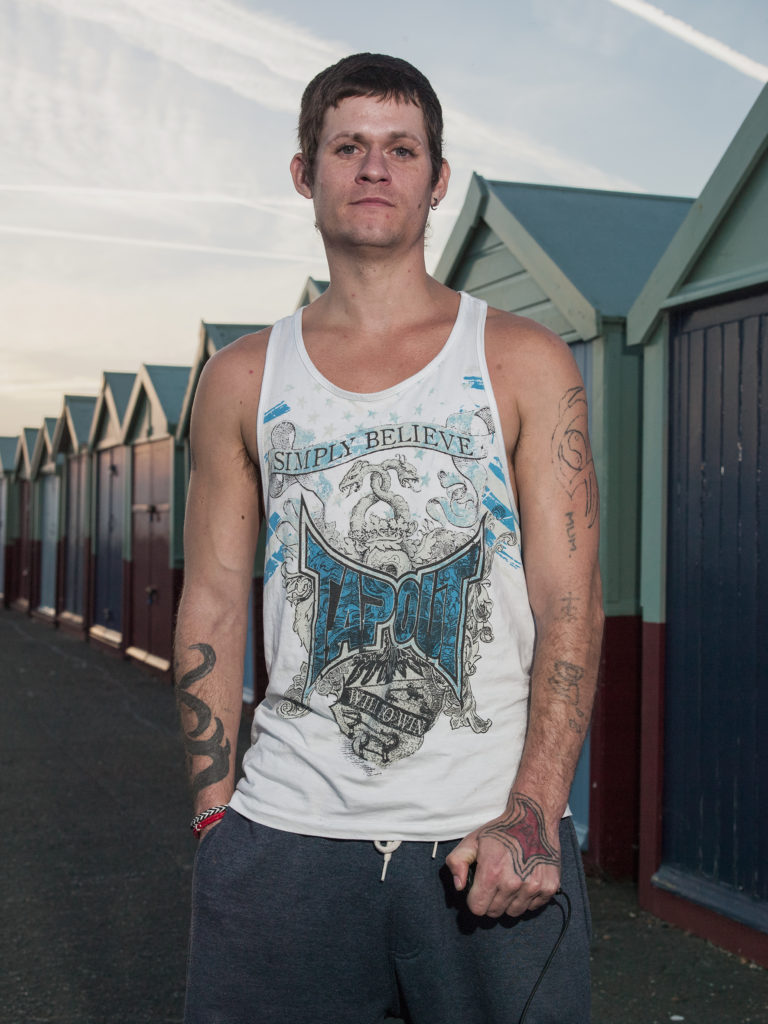

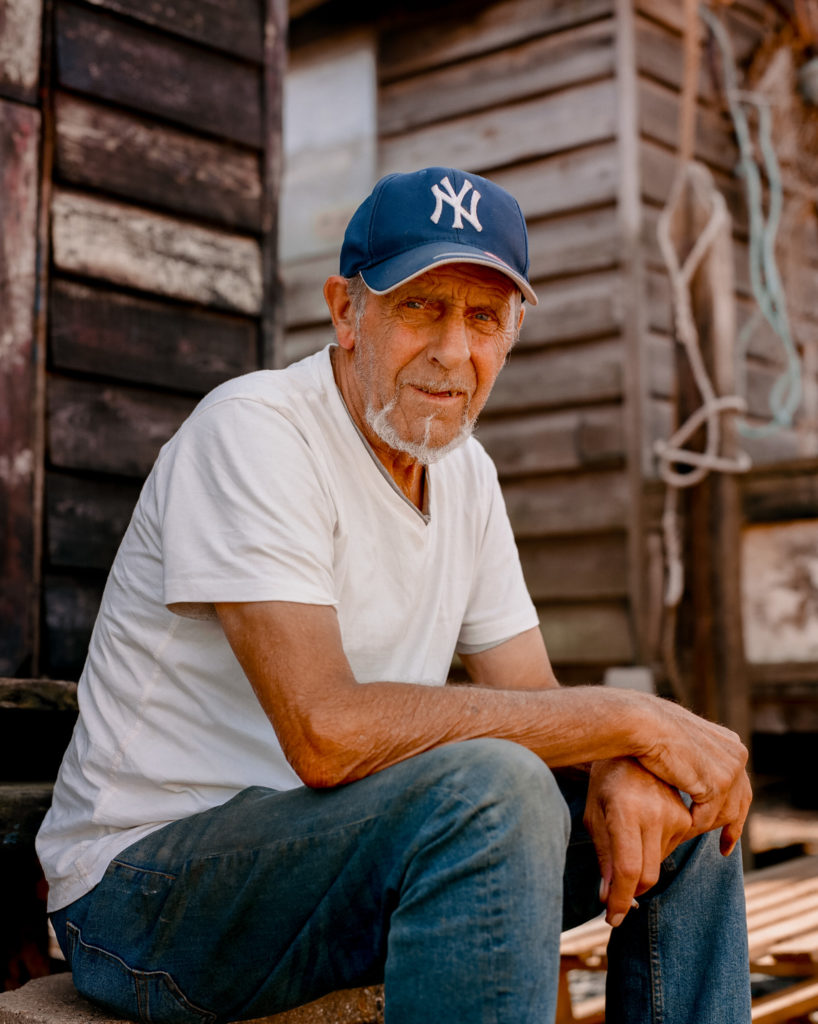

So, the four guys I photographed for this project were studying the same bachelor’s degree as me at Falmouth uni, but funny enough I wasn’t overly close to any of them before the end of our final year. During my interactions with Sam and Matt in particular, I had noticed how their friendship defied the stereotypical male bonds I had observed and researched into, so I approached them about modelling and being fellow photographers were happy to do so. Unlike other straight male friendships, the pair were comfortable to be physically and emotionally intimate with one another yet still very confident in their heterosexual sexuality – I remember finding this friendship inspiring and how this is, or should be, the true representation of masculinity.

It was really lovely to see that over the course of our final year we all became very close friends and I feel this is reflected within the work. Even though the project was founded upon a different relationship, the series also begins to examine my relationship with these guys, and explores not only the boundaries of their own friendships but also their relationship with me; a duality of photographer and subject, but also of queer individual and heterosexual group of ‘lads’.

Lad culture has also impacted the Queer community in different ways. The fetishisation of ‘lads, scally’s and chavs’ are prominent in porn and dating apps. Why do you think the culture has been adopted in such a sexual way?

I remember during my research for the project and my dissertation (an analysis on Laura Mulvey’s male gaze within contemporary culture), there was an essay which hypothesised that the reason some queer individuals have fetishized masculine men it that, on some subconscious level, it is way of regaining power from their oppressor; stereotypically speaking, lads, scallys and chavs all fit this masculine archetype, and are associated as being homophobic, so it could be argued it is a way queer individuals overcome homophobia they’ve face. I don’t necessarily agree whole-heartedly with the theory, but I think it’s thought provoking and raises questions as to why the queer community objectify and are allured to masculine characteristics and traits.

I also, think that society on a broader scale idealise and objectify male beauty who appear to have masculine characteristics and attributes - particularly in western culture. With this in mind, it is incredibly difficult to break-down the queer communities’ complex relationship with fetishising masculinity without analysing society’s relationship of beauty and masculinity.

I grew up attending an all-boys school. Any form of affection or simply caring for another boy you’d be branded as gay and thus the onslaught of insults and demonisation begins. Do you think this embedded part of lad culture means it's hard for those relationships to form?

Yes definitely! This is how the title of the project came to fruition; even though men seem to be more frequently comfortable with each other, there’s a point where it’s too far, “too gay” – and I remember on several occasions where I was in a setting with a group of ‘lads’, and two would be rather intimate before one of them turning around saying “no homo bro”. There always seems to be a degree of resistance when men are too physically or too emotionally intimate with one another, highlighting how ‘toxic masculine’ ideals of male intimacy still seep into society.

From my own experiences as well, I think the environment and context also plays a massive role in men forming close relationships. For instance, I’m more likely to form conversation or friendship with a ‘lad’ in a 1:1 setting as oppose to being in massive group of guys, because usually in large groups of ‘lads’ a form of animalistic competition to impress others, through humiliation of others, begins to occur. Alcohol and drug use can also be a big contributing factor– men who do so, have lowered inhibitions, so care less about their masculine appearance to society and are therefore happy to confide in one another.

Do you think it’s gotten better for straight men within lad culture to open themselves up to someone else in a deeply personal way?

Yes, I think it’s definitely improved, men are more likely to open up and confide in others, more than they would have done even 5 to 10 years ago. Within recent years, there has been a massive light shone on gender and sexuality and there’s been numerous really important discussions about the problematic aspects of masculinity, such as self-reliance and emotional repression, and how this can effect people’s mental health and that confiding in other men isn’t a sign of weakness nor negative thing to do.

However, I think that gendered social constructs are so deeply rooted into our society that it’s going to be really difficult to create systemic change when it is built in the foundations of our society. As recent reports have cited, male suicide rate last year was the highest it had been in almost 20 years, highlighting that even with progress in the mental health sector with programmes in place to prevent suicide, there’s still a lot to be done. But I’m an optimist at heart so I believe that with artists, researchers, councillors etc. studying and challenging the gender and sexuality norms, problematic ideals will dilute and factors which can restrict male friendships will deplete.

Instagram: @ben.ashley.sharp