Darwin Mentorship: Meet Yassen Grigorov

This article contains image descriptions in the captions to help those with visual impairments.

“With time it’s looking more and more like I’m drawn towards work that I feel matters, and stories that I feel need to have a light shone on them”

Starting off with dreams of law school is not typically how you imagine someone’s path in the photography world starting. However this was exactly what happened to Bulgarian born, London based photographer Yassen Grigorov. Yassen is one the six photographers who we are delighted to be working with on the Darwin mentorship programme.

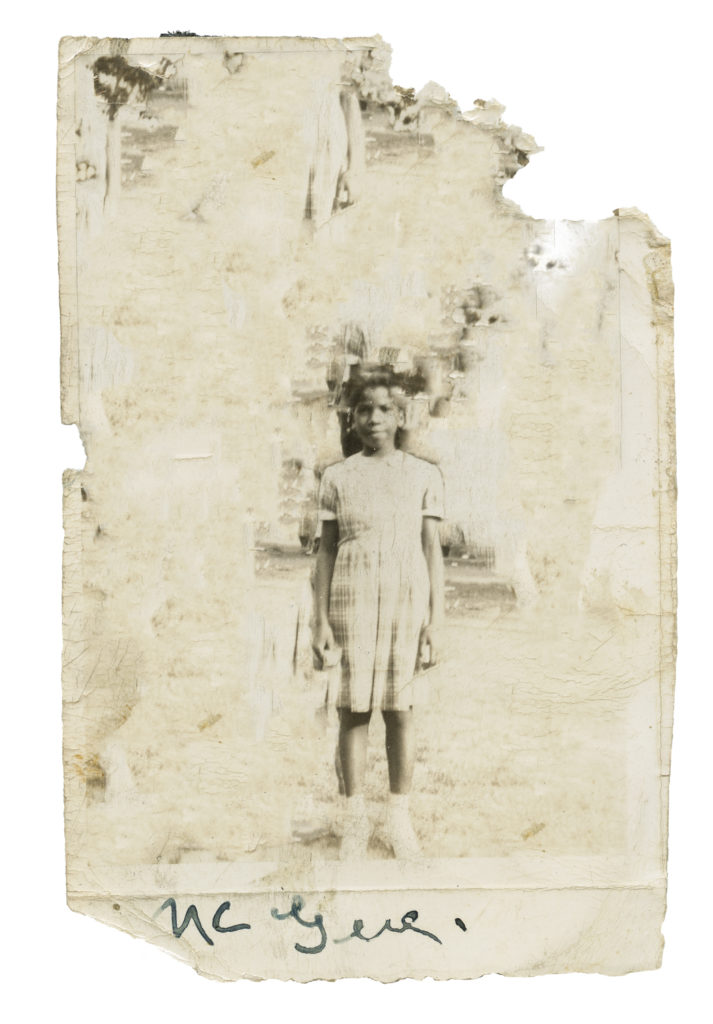

Walking us through his process and love of shooting on analogue cameras, he shares with us his emotional pull to the medium and tactile process that comes along with film photography compared to digital. An example of his analogue approach is Exemplary Home. Exploring the North West of his native Bulgaria, he tells us how the narrative and context drew him in from his safe and objective distance, to creating a personal and emotive bond with the place and project.

Below, Yassen shares with us his photographic processes, inspirations and what he hopes to get from the Darwin mentorship. Read on for a taste of what you can expect to see from Yassen over the coming months.

How did you first get into photography and decide it was the path you wanted to follow?

I started getting into photography about four/five years ago, when I was still in high school in Bulgaria. I sort of fell into it, just shooting on my phone and playing around with photo editing apps. Eventually I got so into it I saved up and got my first DSLR. From then on it really snowballed - I started shooting on manual, joined the photography society at my school and started seeking out the few accomplished professionals in Sofia. Eventually I came to the realisation that I could make a living doing photography, and whilst sharing my craft and vision with the world, so I dropped my plans of getting into law school in Sofia and went all in on an art degree in London instead. Three years later and a first-class BA in the bag, I haven’t looked back and have my sights set ever higher!

| Wow, law to photography is a big change! Does the more law based academic part of you, (so to speak) influence your creative side? I guess so. I didn’t really know what my path was within photography at the beginning, and with time it’s looking more and more like I’m drawn towards work that I feel matters, and stories that I feel need to have a light shone on them, particularly in a documentary framework. I’d imagine this drive towards betterment and meaning is similar to the one found in most legal environments. In practical terms, I suppose there’s also something to be said about my commitment to methodology and research stemming from a similar mindset. |

An integral element of your photographic practice is the use of analogue cameras. How did you get into using analogue and it become your favoured method?

Getting into analog photography almost coincided with a major turning point in my practice. I bought my first film camera - a Zenit EM at the beginning of summer before moving to London. I had already been accepted into Westminster, and knew that analogue would be a big part of the curriculum, so I wanted to gain some insight into it and be a little proactive. I was instantly hooked, and found myself feeling much more attached to the images I made - some of the stuff from my very first roll of film I’d still happily stick up on my wall! A few months down the line, the beginning of winter in London, I bought my first “proper” SLR - a Canon AE-1 that became more or less the exclusive camera I used for the majority of my first year at uni. I also got to try out more or less every relevant film camera under the sun as a part of my degree, so by the time I had access to Hasselblad and Rolleiflex systems, there was no more going back to digital for me. I now own a Pentacon Six TL, which is steadily growing into one of my favourite cameras, and the one I shoot the most often.

As for why I shoot film over digital, it boils down to ontology. Digital images are automated translations of reality. They’re too surgical, too ethereal. I don’t particularly enjoy spending hours colour grading or retouching files, I’d much rather have the physical referent that is an image on emulsion. There’s still a long process in developing, scanning and post production, but at least I know what’s on the film itself is less adulterated than a digital image.

| So would you say you have a more personal, emotional pull and connection to the film images and the process? Absolutely! I feel so much more attached to each shot that I take on film than I do when I work digitally, and I generally feel that tends to be the case for most people that work in a more analogue context. Pressing the shutter and hearing that loud mechanical clunk of the mirror going up, seeing the image in the viewfinder go blank before advancing the lever and having the image return after the lens opens up and the mirror comes back down just leaves much more of a distinctive impression than firing off on burst with autofocus on. That, and the entire risk factor of being able to mess up and not seeing a “completed” image until after developing and scanning it in just makes me grow way more attached than I ever could be to the hundreds of digital files I wind up with after a shoot. When I only have 12 images to work with in a roll each one has to be somewhat special, otherwise I wouldn’t waste the frame - with digital there’s no penalty, and as a result, less value, at least in terms of my process. |

When starting a new project - whether personal or commercial - how do you approach it?

It does depend on the project itself, however I tend to break it down into a decently structured system. The initial stage is always pre-production. If all I have to go off of is an idea, I’ll brainstorm around it and essentially vomit up a bunch of words on a page and start identifying specific themes, narratives, tropes, etc. Once I have my goals for the project decently cleared up and identified, I start thinking about specific shots, different technical aspects, such as what I’m shooting it on and why, the best vessel for the finished work (be it an exhibition, phonebook, online gallery, augmented reality piece, or whatever else). I also begin researching the subject matter, which is a process that generally doesn’t stop until the project is completed, and by that point it usually develops into a field of interest that I keep in touch with on an ongoing basis long after I’ve concluded the work. At the next stage - production - I go and shoot, develop, scan, retouch, etc. Depending on the specific work I might go back and re-shoot. I often tend to arrive at an initial edit and find things that are missing or catch myself digressing and having to reel the work in. And then finally, once I have my finished series or image that I’m happy with, I go back and double check that I’ve achieved what I wanted to achieve, get as much feedback as possible from my peers and followers, and reflect. In reality the process isn’t so formulaic and there’s a lot of going back and forth and bouncing stuff off the walls, but generally speaking I’d say that’s a fair encapsulation of my process️!

Your project, Exemplary Home, perfectly marries a beautiful aesthetic and strong narrative really managing to pull the viewer in and open their eyes to exploring the north-west rural part of Bulgaria. It also seems like a very personal project, linking to your childhood and familial history in the wider context of the country's history. How did you find working with such personal topics? Did you find it hard distancing yourself as a photographer with there being such a strong familial connection?

Exemplary Home as a project was, in a sense, born out of the requirements of my course. It was the final major project for my degree, so when I initially conceptualised and grid-lined it, I didn’t yet know how personal it would become. At that very early stage, I foresaw it as more of a distanced, more objective and conventional documentary project that aimed to educate and inform more than to represent my own experience or indeed presence within that environment. Upon coming back from each shoot and looking at the images I had made, I started to realise that what I was intuitively shooting was in fact way more personal and intimate than that original brief I had given myself, and it actually took a little time to fully embrace that. To answer the question, I didn’t really need to distance myself - it had been almost ten years since I last visited those villages by the time I went back to shoot them. It had been three since I left Bulgaria to carry on my life in London - a decision that was largely influenced by my feelings towards the country and its people at the time. The distance was already there, and by taking on this project I was trying to challenge it. It certainly wasn’t the easiest thing in the world to put a work that wound up being so personal and intimate out there, especially as it involved sharing a lot of the turbulent, personal emotions that motivated what have been the most significant decisions in my life so far, but I believe art has to be honest, genuine and representative of the artist. I wouldn’t have been this happy with the work had the project been less personal.

| You say the distance was already there with Exemplary Home rather than needing to create it. Do you think by the end you actually grew closer to the subject, personally, in some ways? Absolutely. By the time I was going back to shoot that work I was already super open to challenging and changing my view of Bulgaria, however it was the actual experiences I had and the people that I met whilst shooting that contributed so much to it actually working. It wouldn’t be too far to say I fell in love with that environment in a way. Of course, I still don’t want to make excuses for it and I’d still like for it to change, I don’t think its existence is in any ways justified, but I feel like I get it, and by extension the rest of my country, a little bit more now. I feel like I can accept the situation for what it is and focus more on what I can do through my work to help it; certainly the shame and negativity I felt about my roots is gone now. |

What are you hoping to gain from the Darwin mentorship?

In my mind it’s another stepping stone on the path to success. Broadly speaking, I’d love to grow my photographic practice in a more industry-conscious context. The last three years have been about academia and finding my identity and style, whilst picking up an invaluable array of technical, soft and artistic skills along the way. I’m hoping this mentorship will help me achieve my goals not only artistically, but also commercially and help me sustainably grow my practice.

What can we be expecting to see from you in the future?

In the short to mid term, I’ve got a few exhibitions lined up - I’m participating in a show at the Centrala Space in Birmingham in April 2021, and Exemplary Home is having a solo show at the Ko-Op Gallery in Sofia over three weeks between February and March 2021. In a slightly longer term, I’m looking to keep expanding Exemplary Home as a project with the end goal being publishing a large-format photo book of the work.

Beyond that, you can expect more socially and politically conscious documentary work, more authentic analogue photography from the heart, and hopefully more exciting commercial commissions that help brands and fellow creatives visualise their stories and connect with those who matter to them the most!

To see more from Yassen during the mentorship, make sure you are following @darwinmagazine on Instagram To see more of Yassens work, visit www.ygreq.com